Josh Reviews: James Madison: A Biography by Ralph Ketcham

The fourth biography on my quest to read a biography of every president, Ralph Ketcham’s James Madison: A Biography was hugely influential in terms of how I decided to do this project. Daunted by the size of many academic biographies, I chose relatively shorter biographies of Washington and Jefferson. Both of those subjects offered a lot of books to choose from. Many biographies of those two focus on particular events or areas of their life or presidency. John Adams, while somewhat less covered, had also seen a considerable amount of scholarship. Madison has seen significantly less, and his character, while no less complex, was generally kept more private.

This book, however, proved to me just how interesting a biography can be (and how interested I could be even when the writing is painfully academic). Most importantly it showed me just what you can learn about history through biography. A journey through the presidents is an examination of many lives, but it is also a map of the world our ancestors lived in, the things they might have cared about, and the building of the nation that we know today. This book became a blueprint for the kinds of books I sought out in the future: A biography of the president’s entire life, not just their presidency; preferably single volume; academic in nature. This book is an excellent example of all three.

This biography, published in 1971, is the “go-to” or generally accepted best single-volume biography of Madison. Faced with few other options, I dove into the tome, which is thick, heavily and impeccably researched, and admittedly, a bit dry. It was a national book award finalist in 1972.

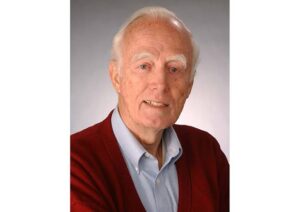

Ralph Ketcham was a professor for nearly 60 years at Syracuse University, and his focus was on political theory, the founding of America, and of course, James Madison. He is the author of of a dozen books on history and political thought. He retired in 1997 and passed away in 2017.

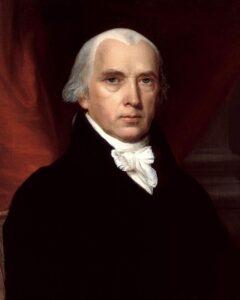

When I read about Jefferson, both in his own biography and the biography of surrounding figures, James Madison often came off as a mere disciple, and less as a man who deserves a high if not commanding position in the totem of early American visionaries. More realistic and down to earth than the gregarious and dream-prone Jefferson, he nonetheless presided over a country in turmoil – a country in it’s early adolescence attempting to define itself by the lives and opinions of the still living and recently dead titans that had founded the nation.

By far the most thorough biography I have yet read of the presidents, this biography still manages to capture the character of a man who was not as immune to the ravages of history or his own mistakes as either Washington or Jefferson. Much more than either of them, however, Madison was an architect of the realities of the republican ideals immortalized in the Constitution, even if he did not think the document was ‘perfect’ in his estimation. Ketcham captures Madison first as a disciple of republicanism and then into his own maturity as possibly the most steadfast and consistent defender of his particular conception of republicanism. Almost no other president was as dedicated to his legalistic ideals and the mechanics of American republicanism.

For a man as private as Madison, his bookishness and less “flashy demeanor” prove a challenge to the modern biographer – he doesn’t have the aura and war-hero reputation of Washington, nor the visionary reputation of Jefferson. This book brings out the man and his virtues out of a complex historical period – an era he played a pivotal role in as secretary of state under Jefferson, active politician in the early 1800s, and the crises of his own presidency, including the disaster of the war of 1812.

Despite his failings, which are neither glossed over in this volume nor given precedence, Ketcham provides us with a deep portrait of a man who is too often relegated to a smaller part in the creation of the nation than he is given credit for. The weaknesses of the book stand one: in sometimes spending too much time on details less relevant to the subject of the telling, and two: in being somewhat less readable than non-academics might benefit from. Still, for those looking for a good single volume on the “father of the constitution”, this biography will more than suffice.

For myself, I learned that I really like a good, thorough, academic biography of a president, and one that attempts as much as possible to be analytical but unbiased.