THG Reviews: “Passionate Sage” By Joseph J. Ellis

Written by Joshua Geiger

As a son of The History Guy and a lover of history I have read many historical books. Several years ago I began a journey to read a biography of every American president, as of March, 2023 I am up to Woodrow Wilson. Passionate Sage was one of the first biographies I read, and stands out as one of the most penetrating on the character and person of its subject.

Joseph J. Ellis is a historian and writer known for writing penetrating

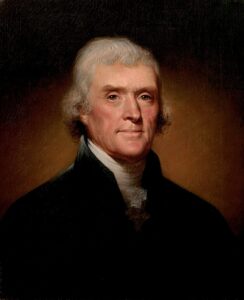

analysis of the inner character of his subjects. His book Founding Brothers won the Pulitzer prize for History in 2001, and his biography of Thomas Jefferson won the National Book Award.

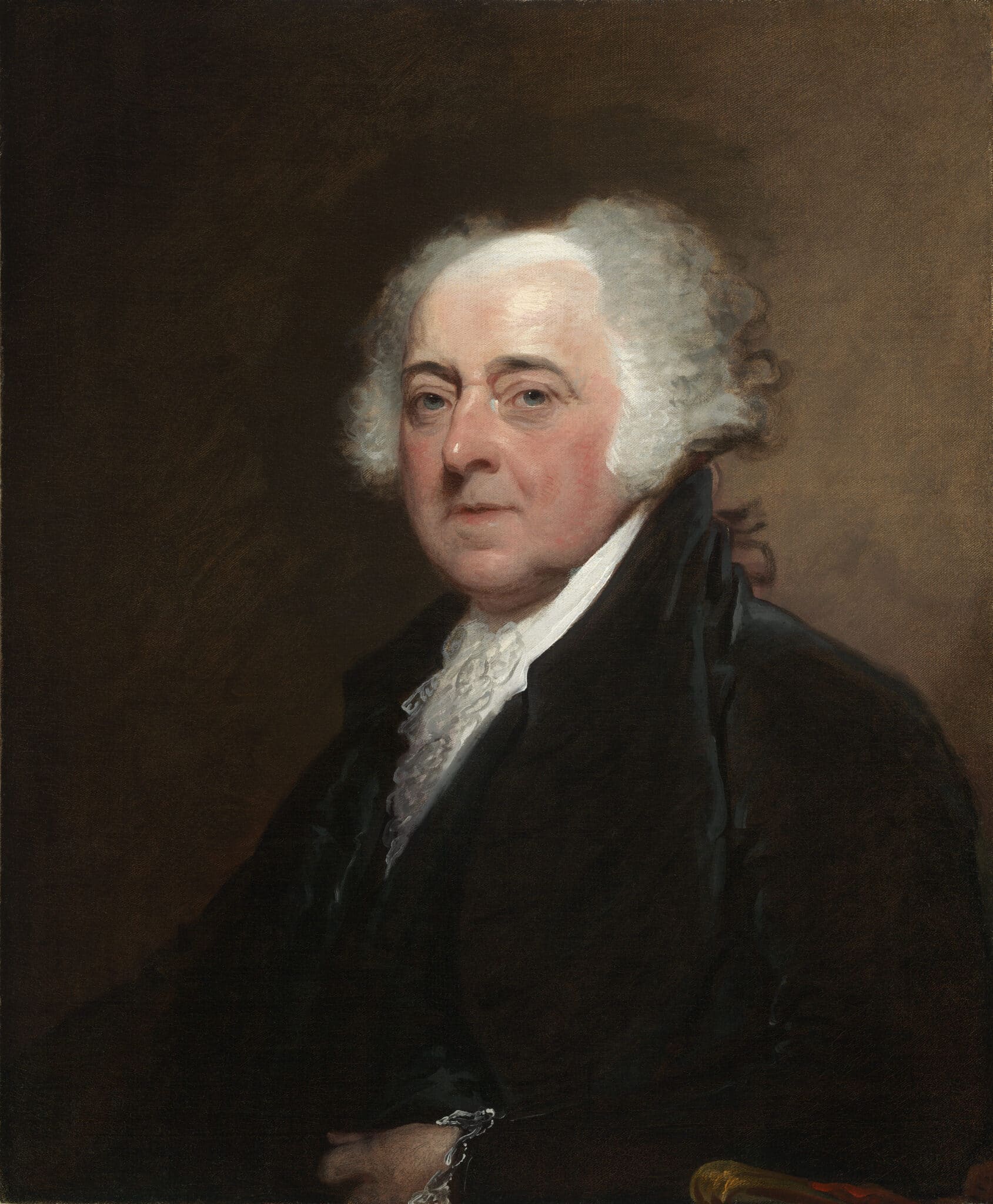

His work on John Adams, published in 1993, is a respected work that helped reignite public interest in Adams. Adams was an interesting man, irascible, cerebral, and in many ways, difficult to personally like. His relationship with Thomas Jefferson, though often overtly adversarial, is perhaps the most important of any relationship among the founding fathers.

On a personal note, Joseph J. Ellis writes biographies that I love reading. His ability to both make the men he writes about feel relevant to the modern age and to analyze both their legacy and character is remarkable. He brings these men out of history, and turns them from marble to flesh. It is fitting, then, that he would do this to a man who warned so furiously against the idea that Americans had overcome what he considered to be the deepest set instincts of man: a search for power, and a tendency toward corruption.

Ellis’ analysis first of what Adam felt and was like gives us an image of an old friend, a pessimistic curmudgeon at times, a prophetic sage at his best. The more recent work by David McCullough doesn’t make this work obsolete; McCullough’s painstaking effort is a detailed biography, but Passionate Sage focuses on describing Adams’ Personality and character. One of my favorite lines in the book describes both what made Adams a powerful but not particularly liked man on the political front, as well as why his historical presence has been so overshadowed by men like Jefferson. This is Ellis’ assertion that Adams was only optimistic when he wanted to be contrary, his every energy devoted to being “the great American caveat.” It is not popular now, and was not popular even then, to view the men of the revolutionary generation, especially Washington, as anything short of semi-mythic. Even in his own lifetime Adams deplored this idea, and considered it ahistorical. His belief was always that the more important revolution was and always would be in the people, and that a title like “The Father of His Country” “belong to no man, but to the American People.”

It was this belief, along with his often unfortunately prophetic pessimism, and his deeply personal and rooted belief that the will of the people is not inherently beyond corruption (a stunningly relevant idea, even today) that made him a caveat in his own time. Ellis expertly and eloquently draws the Adams portrait, by letting us grow attached to Adams’ quirky, personal, and touching traits. He was the only one of the revolutionary generation who was outspoken in his belief that slavery was both morally wrong and would divide the republic, who assumed that women would necessarily be given more rights (if not quite in a modern sense), and the only one who argued so coherently that giving men like him “superhuman qualities… robs their character of consistency and their virtues of all merit.” It was perhaps this, Ellis suggests, that partially shadowed Adams’ legacy, because unlike Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin, Adams could never keep his mouth and his opinions quiet long enough to create the images that his contemporaries carefully groomed.

This book is a treasure for insights into one of the most interesting humans of his generation, even if his belief that “there is no special providence for Americans” isn’t especially patriotic. His inability to let himself be anything but a contrarian on almost every developing national belief would make him an oddity in his own time. His pessimistic warnings about the dangers of what he called the ‘aristocracy’ and the proper role of government would make him attacked in his own time. Still, he held his ground. Power, he believed, was inherently corruptible, but only government could reign in the personal freedoms that Jefferson (and generations of American since) have argued is the single most sacred concept framed into the constitution. It is in that way that this book manages to do its most important duty, one that Adams would be proud of – and that is to be the voice of necessary caution still opposite Jefferson ideals, a cooling mist to the flame of American manifest destiny.

corruptible, but only government could reign in the personal freedoms that Jefferson (and generations of American since) have argued is the single most sacred concept framed into the constitution. It is in that way that this book manages to do its most important duty, one that Adams would be proud of – and that is to be the voice of necessary caution still opposite Jefferson ideals, a cooling mist to the flame of American manifest destiny.

In my mind, one of the most important thing historical works can do is illuminate and challenge established conceptions. Our founding fathers were great men, but it is a disservice to them and to our history not to examine them as people and in the context of their own time. Washington was incredibly aware of what his image could mean to posterity, but it is more valuable to us as lovers of history to examine the man separate from the image, and that we discuss and acknowledge his flaws, both in his own time and by our own standards.

If you enjoy Ellis’ work on Adams, his works on other Revolutionary personalities are similarly incisive examinations of the men that forged the nation. His biography of Washington, His Excellency, is worth reading, as is American Sphinx, his examination of Thomas Jefferson.