Josh Reviews: Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior and President by Ari Hoogenboom

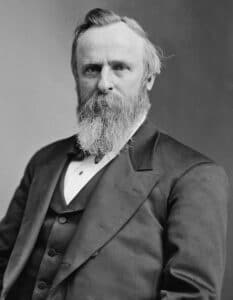

Rutherford Birchard Hayes is one of the presidents who gets lost in the tumult of history (despite his truly excellent beard). Hoogenboom provides us with an illuminating biography, taking advantage of the copious letters and journals that the man left behind, to give us an image of a president who bucks the mold of many: Hayes was a decent man.

Ari Hoogenboom was a long time professor, and taught history from 1965 until his retirement in 1998. He taught at the University of Texas at El Paso, Pennsylvania State, and Brooklyn College. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1965. His works mostly focused on the Gilded Age, including this biography of President Hayes. He also co-wrote a History of Pennsylvania with Phillip Klein.

The reconstruction presidents suffer badly from the difficulty of sectional politics, still deeply embedded in the national consciousness. Hayes was smart enough to see that though he was not an abolitionist, once the Civil War had begun the only possible solution was to end slavery. He saw it as a necessary war goal long before the public at large did, or even the leadership. He was a union man to the end, and saw republican politics in the post-war era as a fight over the legacy of that war.

It complicates his legacy, then, that he was elected in the contested 1876 elections. Hoogenboom’s portrayal of Hayes throughout the crisis is excellent. Put in the precarious position of confirming the results in contested or close elections in several southern states, Hayes ended up confirming his own election while giving up on the last Republican governments in the south in favor of probably unelected but popularly supported democratic governors. The 1876 election is without much doubt the most fraud-filled election in American history. Flatly, not a single one of the Southern states have vote counts that could even slightly be considered legitimate. There was cheating and fraud on both sides, rampant voter intimidation, and many people (mostly black people) killed and injured attempting to vote. It’s truly impossible to determine who won what. The “compromise” that is usually taught is that Hayes was made president (despite Tilden officially winning the Popular vote) and Hayes ended Reconstruction. The truth is not as black and white. Reconstruction likely would have ended either way, as the South was sick of it and the North had grown disinterested. But it is a tragedy that so many people of color in the South who had seen some positive change were so quickly thrown out of office (or simply killed), leading to horrific repression for generations afterward.

While it would be difficult or impossible to determine with certainty, I think that there is a good chance that in an actually fair election Hayes would have won the popular vote and the electoral by a landslide, instead of eking out the slimmest margin of victory in American history (he won by a single electoral vote). I just don’t know that short of outright military occupation that the South could have been quelled. “Local sovereignty” won out in the south.

I think Hoogenboom ends up being a little more kind to Haye’s reform efforts than I would be. It seems likely that Hayes recognized the utility of a partisan government, and that his reticence to overhaul the system was not as unintended as the author would make us believe. Still, while overshadowed by so many things in the “Gilded Age” American scene, Hayes was a more or less competent president, who made a good faith effort to reduce corruption. (I agree with Hoogenboom that Hayes did not know about the post office scandal stuff. Like Grant, his presidency was tarnished by corruption that was discovered after the fact but present long before).

Why I think Hayes is worth remembering though, is less for his generally competent if uneventful presidency and more for his commitment to public education through the Peabody group and his efforts to improve the education of both whites and blacks (even if his belief that the “better part” of the South would rise above racism and discrimination was almost hopelessly naive.)

This book brought me to the conclusion that I like Hayes as a person – refusing public office when he could be fighting, his faith in the union, and his belief in public education as an equalizing force, as well as his commitment to help blacks in his post-presidential years – make him stand out as a man of better character than most – and that is worth remembering.