Josh Reviews: John Tyler, the Accidental President by Edward Crapol

Most modern Americans, if pressed to remember a single thing about Tyler, would think only that he wasn’t very good. This book definitely helps to rescue Tyler from the darkness, and Crapol does a serviceable job with his thesis, which is to use Tyler’s tragic failures as a kind of metaphor for the wider failures and anachronisms of the south. My first complaint was that Crapol spent very little time on Tyler’s youth; I tend to enjoy seeing how the presidents spent their early lives, usually before they set their eyes on the presidency. Overall I think its a fairly minor criticism, however.

Most modern Americans, if pressed to remember a single thing about Tyler, would think only that he wasn’t very good. This book definitely helps to rescue Tyler from the darkness, and Crapol does a serviceable job with his thesis, which is to use Tyler’s tragic failures as a kind of metaphor for the wider failures and anachronisms of the south. My first complaint was that Crapol spent very little time on Tyler’s youth; I tend to enjoy seeing how the presidents spent their early lives, usually before they set their eyes on the presidency. Overall I think its a fairly minor criticism, however.

Edward P Crapol was a distinguished professor of history, and a professor emeritus at the College of William and Mary. He also wrote a biography of James Blaine, an important figure of the era who never made it to the presidency (not for lack of trying). Unlike several of the preceding biographies, this was a much more recent book – published in 2006 – and in many ways is more readable and interesting for it. There is a more recent biography of Tyler that blogger Stephen Floyd reviewed very well. (Floyd has read a LOT more biographies than me, and is my go-to for advice on what book I want to pick next).

Here are some things that Tyler did that this book taught me: Despite his strict constructionist views, Tyler helped to hugely grow the strength of the executive and threaten legislative dominance. He used secret service funds to avoid congressional oversight, in paying Duff Green to be his “ambassador of slavery” in England, and in (probably) using agents in the Dominican/Haitian war. He dramatically increased presidential war powers by promising Texas military protection and moving troops to prove it.

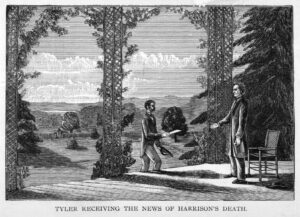

Tyler’s most important contribution to history is the “Tyler precedent” which forever instituted the precedent of VPs becoming president if the President vacates the seat. But he also was a driving and effective force in Pacific diplomacy, making definitive moves to secure Hawaii within the US sphere of influence, gaining access to China, using missionaries and civilians as political tools, and insisting on official protection of US citizens abroad.9993

He wasn’t an incredible president. Crapol certainly does his best to paint Tyler kindly, and honestly too much at times – my largest complaint is that Crapol insists any later president arguing for Jeffersonian expansionism and American exceptionalism is echoing Tyler precedent. Tyler also bumbled quite a bit with his diplomacy with England. His use of joint-resolution instead of Senate treaty ratification in annexing Texas had long-term effects that fairly clearly were extra-constitutional. Worst, and probably best presented in this book, Tyler chose slavery over the Union. Crapol really does try to minimize this by pointing to Tyler’s early statements about the moral issues with slavery. While not inaccurate, it is also true that in the end, Tyler is the only traitor president (he voted for Virginia to secede) in US history because he really did believe in slavery as an institution.

The tragic thing for the union was that slavery became more important than anything else, for Tyler and many others in the south. Quotes from the text to support this are abundant: in 1860, Lincoln was asked to give up his victory. He said “we are told in advance, the government shall be broken up, unless we surrender to those we have beaten, before we take office.”(p258). He pointed out accurately that “[they] will repeat the experiment on us ad libitum. A year will not pass, till we shall have to take Cuba as a condition upon which they will stay in the union.” The driving wedge of slavery was most important in the South’s growing certainty in slavery as a positive good (a shift from earlier concepts of it being a “necessary evil”, constantly argued and more and more believed by whites in the south) and the refusal to consider it as a moral issue. They pushed for empire, like Tyler, because they believed that continuing to move West (and south, and etc.) was necessary as a ‘safety valve’ for the union, largely as a distraction from slavery as a central political point. Even by the 1820s, despite widespread beliefs, the idea of ‘diffusion’ was nonsense(it was mistaken view also shared by Jefferson, who hoped that slavery would fade away). The south wished to grow and to continue their spread of a slave republic, and the North was becoming a serious impediment to that dream. Growing international pressure pressed the North, who pressed the South, who entrenched. Their arguments became more and more hysterical.

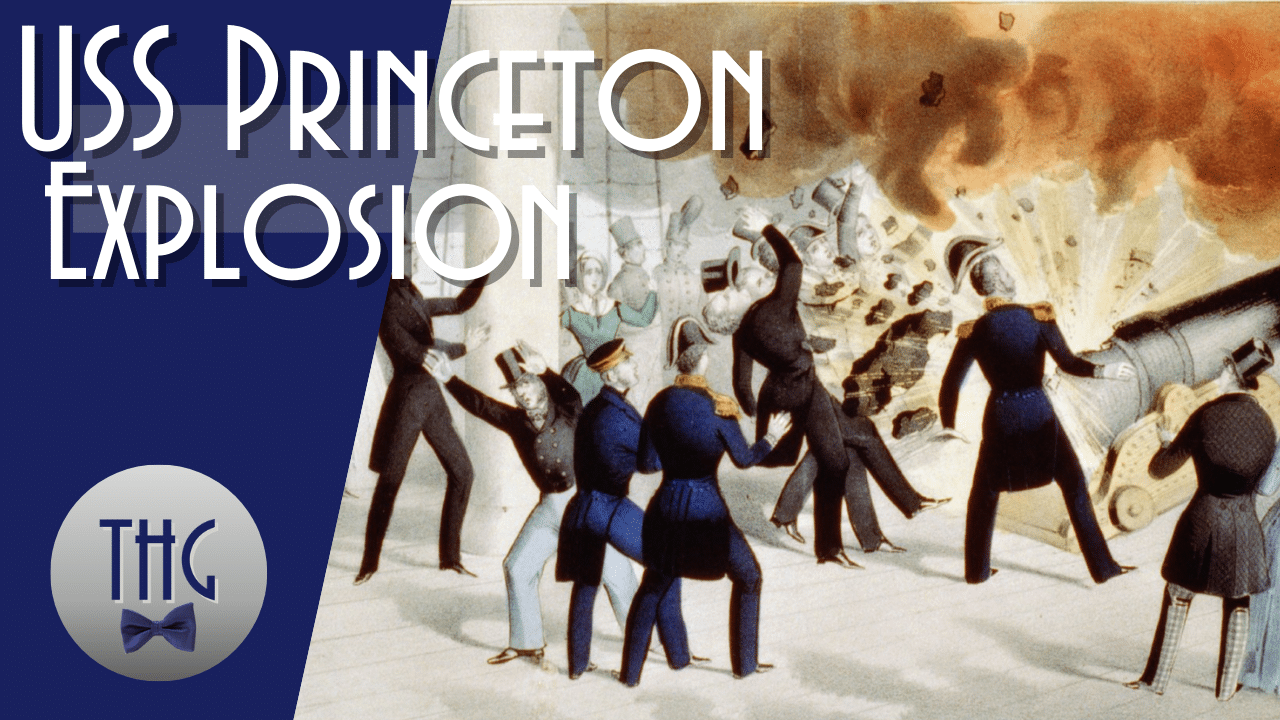

Tyler was a unique president in many ways – he had left the Democratic party, and became an important piece of the Whig strategy to win the 1840 election by garnering support in the south. He ended up essentially presiding over the disintegration of the Whig party, and didn’t act like a Whig as president – politically, of course, most of his views were much more in line with the Democratic South. But he had burned all of his bridges in the Democratic party, leaving him without allies when he was unexpectedly thrust into the highest office in the land. He also faced one of the most serious disasters of any president in American history in the Princeton explosion, which killed two cabinet members (that story was the subject of a History Guy Episode).

Tyler left the union and became the only traitor president. The North was standing in the way of the growth of the US, and most importantly, they were preventing the spread of slavery. The fact was that the Southern states had become incompatible with union. The north was not less racist than the south, or any more happy to live with blacks on even footing. But the south made it their sine qua non – that their destiny, slavery included, could not be trod upon by any force or threat, including the abolitionists. This is relevant because Tyler’s life serves as an excellent illustration of how the mood shifted. This was the tragedy of Tyler and the south: as Crapol says, “president Tyler rejected that vision of the future and abandoned both the union and his lifelong pursuit of national destiny…[he betrayed] his loyalty and commitment to what he had once defined as “the first great American interest” – the preservation of the union.”(p283). (As a side note, I think this supports my thinking of how Jackson might have felt about secession in 1860.) Once slavery became more important than the republic and the union, war was unavoidable.

Overall, this is a really good biography. It is not necessarily the ‘perfect’ kind of biography since it focuses too little on Tyler’s personal life and his youth, but it covers Tyler’s presidency and post-presidency well and highlights some very important pieces of American history.