Josh Reviews: Franklin Pierce Vol 1 and 2 by Peter Wallner

Up until this point, I had only ready single-volume biographies, although numerous multi-volume biographies exist about previous presidents. I prefer a single volume primarily because it’s simply easier to read, and generally the more volumes, the more unreadably academic I feared the biography would be. But like many of his contemporaries and immediate predecessors, there is not exactly a lot of choices for Franklin Pierce, making him the first president I read more than one book about, as odd as that might seem. These books are also fairly difficult to get a hold of compared to some, which is too bad given there’s little else to read about Pierce.

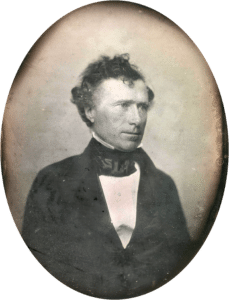

Peter Wallner is an author and educator, and for many years the library director for the New Hampshire Historical Society. He has a doctorate in American history from the Pennsylvania State University. This biography Pierce was the first in three quarters of a century to be a true, scholarly examination of the poor president (the last was published in 1931). As Wallner points out, there are some unique points about Pierce – he was at the time the youngest president ever at 48 years old, and he is the only President to hail from New Hampshire. While Wallner claims he is “no apologist” I can’t help but feel he goes to bat pretty hard for Pierce in his two volumes: New Hampshire’s Favorite Son and the unambiguously titled Martyr for the Union.

Judging a man as a person, while trying to understand his decisions and put them in a historical context, is not an easy feat. Pierce had opinions that were abysmal, both by modern standards and in the judgement of history. He struggled with alcohol abuse and faced some very terrible personal tragedies. He was a bad president by almost any measure. It’s difficult to take all of that and come up with a single, concise summary about how we should feel about him, even if we can unequivocally condemn some of it. People, and history, are complicated.

The first book, New Hampshire’s Favorite Son, focuses entirely on Pierce’s pre-presidential career.

Well-researched if perhaps overly complimentary, this book does a good job of answering one of the questions that most interests me about presidents: why were they elected in the first place?

Pierce is presented as a moderate in this book, who was looking constantly for a way to secure first and foremost, union. I think it’s a little difficult to maintain that that was his only and unwavering goal (or perhaps he was simply deluded), but if Pierce was anything, he was a party man. For the Democratic party in the 1840s and 50s, that meant he abhorred abolitionism as a ‘threat to union’. In practice what this meant is supporting slave-states and slave owner rights. Pierce wasn’t an unlikable guy, though, and while undistinguished as a senator served his party well in New Hampshire, and had strong beliefs around religious freedom (of Shakers) that were notable at the time due to rampant nativist and anti-catholic feeling.

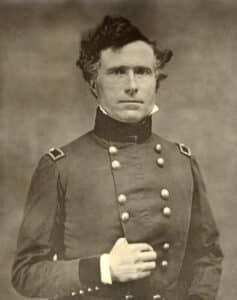

Like Polk, Pierce gave lip service to the whole “I didn’t want to be president, just waited until called” while managing an underground of supporters and political wizardry to make himself the compromise candidate for the presidency. That’s true of many of the “compromise” candidates in this era – as the more capable and well-known possibilities simply turned one or another constituency away, these “dark horse” figures waited for their chance to present themselves as someone who could appeal more broadly; Pierce was selected only after nearly 50 ballots at the democratic convention. He is also a very tragic figure, when his only surviving son dies mere weeks away from his inauguration. This book does much to rescue him from obscurity, which I love. A good part of my interest is knowing that really, people don’t ‘accidentally’ become president. They are in the position just to be nominees for a reason, and Pierce is no exception.

Martyr for the Union picks up where the last volume left off, essentially at Pierce’s inauguration. It was a difficult time to be president, and the sectional issues of the country were ramping up to a fever pitch. I don’t honestly know who could have lead the country through that, and I don’t think any leader could have prevented the coming war, but I can promise you that Pierce was the wrong man for the job. Wallner puts the strongest, most noble face on Pierce’s presidency, but even that leaves a difficult record to defend. Personally, I think this book suffers under the weight of its pro-Pierce advocacy. Wallner mostly brushes off Pierce’s drinking, refusing to bring it up as a facet of Pierce’s struggles most of the time. In the end, the best that Wallner can say is that Pierce “was the best the nation could have hoped for at the time”.

I think I agree with Wallner that while the presidents leading up to the civil war are seen as a series of blunders, it’s very possible there was no possible course that could have avoided the war. Wallner gives Pierce much credit in trying to cool the situation, but I am a little more critical. While I think that Pierce’s belief in the constitution (and its protection of slavery) as well as his idea of ‘union’ were sincerely held, I don’t know that his attempts to steer a middle course in domestic matters were successful or even well advised. His belief that internal matters were the responsibility of the states kept Kansas at the forefront of the nation and kept the coals of chaos burning there – his handling of that situation was inept and biased, and it got people killed. His possibly laudable goal of evenly distributing patronage appointments among the various democratic factions was always a bad idea, and was absolutely doomed to weaken his party and his own support.

That said, Pierce was not a president without successes, and Wallner might be correct in claiming that besides slavery, Pierce would be considered a good president; not a great one, but at least a competent one. The problem is we are talking about a time that you simply can’t remove slavery from the equation. It was THE issue to nearly everybody. Pierce did stick to Democratic principles in lowering the tariffs, fighting for American neutrality, and lowering the public debt. He managed some diplomatic successes including gaining fishing rights in Canada and even half-way managed a crisis in Nicaragua, though his treaty was never passed. Those accomplishments were not done without tribulations, though, and Pierce’s choices for many of his foreign appointments were poorly made. Pierre Soule was a dismal ambassador, and between offending the Spanish and the Ostend Manifesto caused nothing but problems for Pierce. Pierce’s choices of messengers to Gadsden would embarrass his administration when the treaty included government endorsement for one of the trans-isthmian companies vying for recognition from Mexico. Those were not unavoidable, but illustrative of his weakness as an executive.

By far Pierce’s greatest weakness, though, is displayed in the Kansas fiasco. How much of the blame lies on his shoulders, and how much of it should be explained as an unavoidable symptom of the situation is unclear, but Pierce’s choices of governors proved only to exacerbate the situation and his indecision in course only inflamed it more. He and the democrats were also outspoken critics mostly of abolitionist attempts to take over Kansas, while they took for granted that pro-slavery forces were just ‘defending their rights’. Neither side was without guilt, but it was the ‘free-state’ forces that were most harmed by Pierce’s administration, and when he did try to steer a more middle course it only succeeded in being unfair to pretty much everyone. Even the brief peace attained in 1856 was illusory; it’s impossible to see “burning Kansas” as anything but a dismal and dramatic failure on the part of his administration. It was also under Pierce that the government officially decided that the Compromise of 1850 fully overrode the Missouri Compromise.

Most disturbing about this read, though, is how difficult it is to form a permanent opinion of Pierce. He was certainly an unapologetic racist, and some of his quotes are wildly offensive to modern sensibility. He stood for slave-state rights no matter what, and not uncommonly for northern men, was rabidly white-supremacist. But at least with other Northern presidents during the war you could give them some credit for sounding like above-average moralists on the issue. Fillmore, even though he had similar constitutional defenses for slavery, was never as offensive, and even Van Buren eventually campaigned with abolitionists. Pierce never did, and even after the war wished to curtail freedmen rights.

Despite all of that, though, for a man of his time Pierce was a man of surprisingly strong convictions and loyalty, a generous friend to the like of Nathaniel Hawthorne and his children, an often empathetic soul, and a defender of religious liberty and immigrant rights. He did try to push a middle ground, and his constitutional beliefs were sincerely held, even when it pushed him to veto Democratic legislation on things like internal improvements. His cabinet was solid (according to Wallner, the only cabinet in history that had no changes in a full four-year term) and largely unselfish, pushing to reform and modernize departments and stomp out fraud. He also was a singularly tragic figure, who lost all three of his children (the oldest and last, at 11, to a train accident he had to witness) and who endured the hatred and accusations of his country during the civil war. In the end, he would die without family by his side, a victim of his own drinking. Still, he had made lifelong friends and had loyal, doting supporters, though they may have been few, that knew him personally. So was Pierce a bad man? It is difficult to say if he was ALL bad . Was he a bad president? That also is difficult to say – for his course, though ineffective, may truly have been the best we could have hoped for at the time.